London Underground milestones

| 1843 Constructed by Sir Marc Brunel and his son Isambard, the Thames Tunnel opens |

| 1863 On 10 January, The Metropolitan Railway opens the world's first underground railway, between Paddington (then called Bishop's Road) and Farringdon Street |

| 1868 The first section of the Metropolitan District Railway, from South Kensington to Westminster (now part of the District and Circle lines), opens |

| 1869 The first steam trains travel through the Brunels' Thames Tunnel |

| 1880 Running from the Tower of London to Bermondsey, the first Tube tunnel opens |

| 1884 The Circle line is completed |

| 1890 On 18 December, The City and South London Railway opens the world's first deep-level electric railway. It runs from King William Street in the City of London, under the River Thames, to Stockwell |

| 1900 The Prince of Wales opens the Central London Railway from Shepherd's Bush to Bank (the 'Twopenny Tube'). This is now part of the Central line |

| 1902 The Underground Electric Railway Company of London (known as the Underground Group) is formed. By the start of WWI, mergers had brought all lines - except the Metropolitan line |

| 1905 District and Circle lines become electrified |

| 1906 Baker Street & Waterloo Railway (now part of the Bakerloo line) opens and runs from Baker Street to Kennington Road (now Lambeth North). Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (now part of the Piccadilly line) opens between Hammersmith and Finsbury Park |

| 1907 Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway (now part of the Northern line) opens and runs from Charing Cross to Golders Green and Highgate (now Archway). Albert Stanley (later Lord Ashfield) is appointed General Manager of the Underground Electric Railway Company of London Limited |

| 1908 The name 'Underground' makes its first appearance in stations, and the first electric ticket-issuing machine is introduced. This year also sees the first appearance of the famous roundel symbol |

| 1911 London's first escalators are installed at Earl's Court station |

| 1929 The last manually-operated doors on Tube trains are replaced by air-operated doors |

1933

|

| 1940 Between September 1940 and May 1945, most Tube station platforms are used as air raid shelters. Some, like the Piccadilly line, Holborn - Aldwych branch, are closed to store British Museum treasures |

| 1948 The London Passenger Transport Board was nationalised and now becomes the London Transport Executive |

| 1952 The first aluminium train enters service on the District line |

| 1961 Sees the end of the steam and electric locomotive haulage of London Transport passenger trains |

| 1963 The London Transport Executive becomes the London Transport Board, reporting directly to the Minister of Transport |

| 1969 The Queen opens the Victoria line |

| 1970 The London Transport Executive takes over the Underground and the Greater London area bus network, reporting to Greater London Council |

1971

|

| 1975 A fatal accident on the Northern line at Moorgate kills 43 people. New safety measures were introduced |

| 1977 The Queen opens Heathrow Central station (Terminals 1 2 3) on the Piccadilly line |

| 1979 The Prince of Wales opens the Jubilee line |

| 1980 A museum about the birthplace of modern urban transportation, called Brunel Engine House, opens to the public |

| 1983 Dot matrix train destination indicators introduced on platforms. |

| 1984 The Hammersmith & City and the Circle lines convert to one-person operation |

| 1986 The Piccadilly line is extended to serve Heathrow Terminal 4 |

| 1987 A tragic fire at King's Cross station kills 31 people |

| 1989 New safety and fire regulations are introduced following the Fennell Report into the King's Cross fire |

| 1992 The London Underground Customer Charter is launched |

1993

|

1994

|

1999

|

2003

|

| 2005 52 people are killed in bomb attacks on three Tube trains and a bus on 7 July |

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

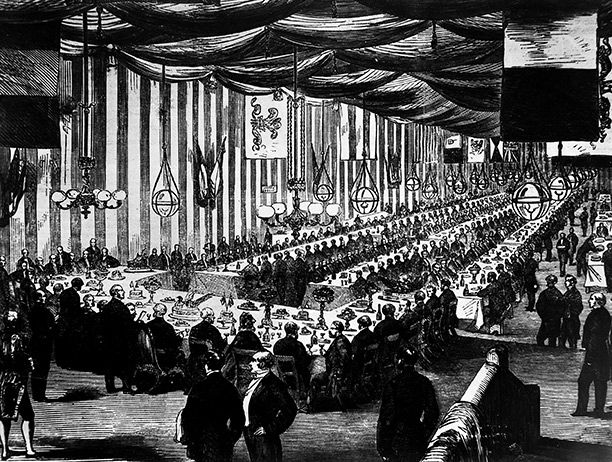

The capital went underground on January 10th, 1863.

Train

time tables: the banquet at Farringdon Street station to mark the

opening of the Metropolitan Railway, from the 'Illustrated London News'.

London Transport MuseumWork on the world’s first

underground railway started in 1860 when the Metropolitan Railway began

building a tunnel more than three miles long from Paddington to

Farringdon Street. It was largely financed by the City of London, which

was suffering badly from horse-drawn traffic congestion that was having a

damaging effect on business. The idea of an underground system had

originated with the City solicitor, Charles Pearson, who had pressed for

it for years. It was he who persuaded the City Corporation to put up

money and he was probably the most important single figure in the

underground’s creation. He died in 1862, only a few months before his

brainchild came to life.

Train

time tables: the banquet at Farringdon Street station to mark the

opening of the Metropolitan Railway, from the 'Illustrated London News'.

London Transport MuseumWork on the world’s first

underground railway started in 1860 when the Metropolitan Railway began

building a tunnel more than three miles long from Paddington to

Farringdon Street. It was largely financed by the City of London, which

was suffering badly from horse-drawn traffic congestion that was having a

damaging effect on business. The idea of an underground system had

originated with the City solicitor, Charles Pearson, who had pressed for

it for years. It was he who persuaded the City Corporation to put up

money and he was probably the most important single figure in the

underground’s creation. He died in 1862, only a few months before his

brainchild came to life.The first section linked the City with the railway stations at Paddington, Euston and King’s Cross, which had been built in the previous 30 years. The chief engineer was John Fowler, the leading railway engineer of the day, who would go on to create the Forth Bridge in Scotland. He did not come cheap and his Metropolitan Railway salary of £137,700 would be worth about £10 million today.

A deep trench was excavated by the ‘cut and cover’ method along what are now the Marylebone Road and the Euston Road and turning south-east beside Farringdon Road. Brick walls were built along the sides, the railway tracks were laid at the bottom and then the trench was roofed over with brick arches and the roads were put back on top, though the last stretch to Farringdon was left in an open, brick-lined cutting. Stations lit by gas were created at Paddington, Edgware Road, Baker Street, Great Portland Street, Euston Road and King’s Cross on the way to Farringdon, which was at ground level and was built, not entirely inappropriately as things turned out, on the former site of the City cattle market. W.E. Gladstone, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, and his wife Catherine were passengers on a trial trip in May 1862.

Built round the clock by shifts of navvies, the line had to avoid numerous water and gas pipes, drains and sewers. There was a problem when the noxious Fleet Ditch sewer flooded the works in Farringdon Road, but that was dealt with and on January 9th, 1863 the line’s completion was celebrated at a gathering of railway executives, Members of Parliament and City grandees including the lord mayor. The prime minister, Lord Palmerston, had declined his invitation, saying that at 79 he wanted to stay above ground as long as he could. Starting from Paddington, some 600 guests were carried in two trains along the line to Farringdon Street station, where a banquet was held, speeches made and due tribute paid to the memory of Charles Pearson. Music was provided by the Metropolitan Police band.

The line was opened to the public on the following day, a Saturday, and people flocked to try it out. More than 30,000 passengers crowded the stations and pushed their way into packed trains. The underground had been mocked in the music halls and derisively nicknamed ‘the Drain’. There were predictions that the tunnel’s roof would give way and people would fall into it, while passengers would be asphyxiated by the fumes, and an evangelical minister had denounced the railway company for trying to break into Hell.

In fact the railway was a tremendous success and The Times hailed it as ‘the great engineering triumph of the day’. In its first year it carried more than nine million passengers in gas-lit first-class, second-class and third-class carriages, drawn by steam locomotives that belched out choking quantities of smoke. The fact that the passengers were at first forbidden to smoke in the carriages was not much help.

Over the next two years the line was extended further east into the City to Moorgate and, in the other direction, to Hammersmith. Other lines were soon added to the growing network, deeper underground tunnelling was introduced and the steam trains were replaced by electric trains. The first underground electric railway, the City and South London, which ran from near the Bank of England under the Thames to the South Bank, opened in 1890. It was the first line to be called ‘the tube’ and the windowless carriages with their heavily upholstered interiors were popularly known as ‘padded cells’.

As far as the City was concerned, the corporation was able to sell its shares in the Metropolitan Railway at a profit and the underground did ease congestion for a time. A more lasting consequence was to make commuting far easier and so cause London to sprawl out even more from its centre, while the number of people actually living in the City itself declined sharply.

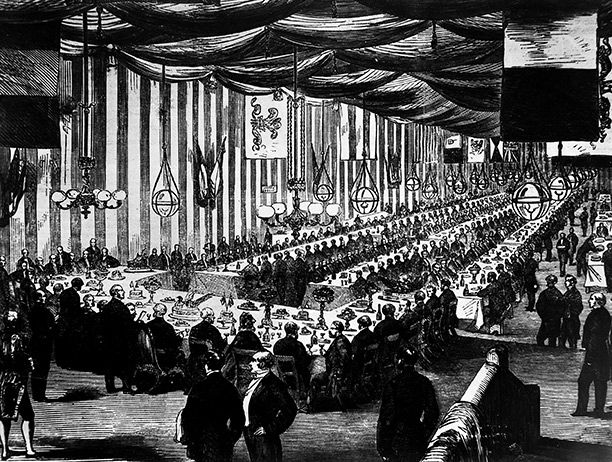

The capital went underground on January 10th, 1863.

Train

time tables: the banquet at Farringdon Street station to mark the

opening of the Metropolitan Railway, from the 'Illustrated London News'.

London Transport MuseumWork on the world’s first

underground railway started in 1860 when the Metropolitan Railway began

building a tunnel more than three miles long from Paddington to

Farringdon Street. It was largely financed by the City of London, which

was suffering badly from horse-drawn traffic congestion that was having a

damaging effect on business. The idea of an underground system had

originated with the City solicitor, Charles Pearson, who had pressed for

it for years. It was he who persuaded the City Corporation to put up

money and he was probably the most important single figure in the

underground’s creation. He died in 1862, only a few months before his

brainchild came to life.

Train

time tables: the banquet at Farringdon Street station to mark the

opening of the Metropolitan Railway, from the 'Illustrated London News'.

London Transport MuseumWork on the world’s first

underground railway started in 1860 when the Metropolitan Railway began

building a tunnel more than three miles long from Paddington to

Farringdon Street. It was largely financed by the City of London, which

was suffering badly from horse-drawn traffic congestion that was having a

damaging effect on business. The idea of an underground system had

originated with the City solicitor, Charles Pearson, who had pressed for

it for years. It was he who persuaded the City Corporation to put up

money and he was probably the most important single figure in the

underground’s creation. He died in 1862, only a few months before his

brainchild came to life.The first section linked the City with the railway stations at Paddington, Euston and King’s Cross, which had been built in the previous 30 years. The chief engineer was John Fowler, the leading railway engineer of the day, who would go on to create the Forth Bridge in Scotland. He did not come cheap and his Metropolitan Railway salary of £137,700 would be worth about £10 million today.

A deep trench was excavated by the ‘cut and cover’ method along what are now the Marylebone Road and the Euston Road and turning south-east beside Farringdon Road. Brick walls were built along the sides, the railway tracks were laid at the bottom and then the trench was roofed over with brick arches and the roads were put back on top, though the last stretch to Farringdon was left in an open, brick-lined cutting. Stations lit by gas were created at Paddington, Edgware Road, Baker Street, Great Portland Street, Euston Road and King’s Cross on the way to Farringdon, which was at ground level and was built, not entirely inappropriately as things turned out, on the former site of the City cattle market. W.E. Gladstone, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, and his wife Catherine were passengers on a trial trip in May 1862.

Built round the clock by shifts of navvies, the line had to avoid numerous water and gas pipes, drains and sewers. There was a problem when the noxious Fleet Ditch sewer flooded the works in Farringdon Road, but that was dealt with and on January 9th, 1863 the line’s completion was celebrated at a gathering of railway executives, Members of Parliament and City grandees including the lord mayor. The prime minister, Lord Palmerston, had declined his invitation, saying that at 79 he wanted to stay above ground as long as he could. Starting from Paddington, some 600 guests were carried in two trains along the line to Farringdon Street station, where a banquet was held, speeches made and due tribute paid to the memory of Charles Pearson. Music was provided by the Metropolitan Police band.

The line was opened to the public on the following day, a Saturday, and people flocked to try it out. More than 30,000 passengers crowded the stations and pushed their way into packed trains. The underground had been mocked in the music halls and derisively nicknamed ‘the Drain’. There were predictions that the tunnel’s roof would give way and people would fall into it, while passengers would be asphyxiated by the fumes, and an evangelical minister had denounced the railway company for trying to break into Hell.

In fact the railway was a tremendous success and The Times hailed it as ‘the great engineering triumph of the day’. In its first year it carried more than nine million passengers in gas-lit first-class, second-class and third-class carriages, drawn by steam locomotives that belched out choking quantities of smoke. The fact that the passengers were at first forbidden to smoke in the carriages was not much help.

Over the next two years the line was extended further east into the City to Moorgate and, in the other direction, to Hammersmith. Other lines were soon added to the growing network, deeper underground tunnelling was introduced and the steam trains were replaced by electric trains. The first underground electric railway, the City and South London, which ran from near the Bank of England under the Thames to the South Bank, opened in 1890. It was the first line to be called ‘the tube’ and the windowless carriages with their heavily upholstered interiors were popularly known as ‘padded cells’.

As far as the City was concerned, the corporation was able to sell its shares in the Metropolitan Railway at a profit and the underground did ease congestion for a time. A more lasting consequence was to make commuting far easier and so cause London to sprawl out even more from its centre, while the number of people actually living in the City itself declined sharply.

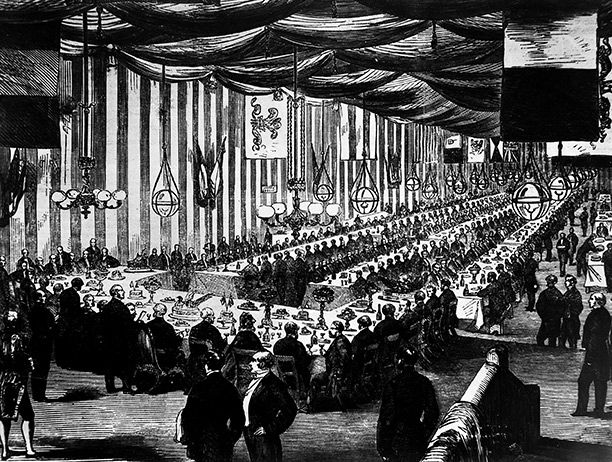

The capital went underground on January 10th, 1863.

Train

time tables: the banquet at Farringdon Street station to mark the

opening of the Metropolitan Railway, from the 'Illustrated London News'.

London Transport MuseumWork on the world’s first

underground railway started in 1860 when the Metropolitan Railway began

building a tunnel more than three miles long from Paddington to

Farringdon Street. It was largely financed by the City of London, which

was suffering badly from horse-drawn traffic congestion that was having a

damaging effect on business. The idea of an underground system had

originated with the City solicitor, Charles Pearson, who had pressed for

it for years. It was he who persuaded the City Corporation to put up

money and he was probably the most important single figure in the

underground’s creation. He died in 1862, only a few months before his

brainchild came to life.

Train

time tables: the banquet at Farringdon Street station to mark the

opening of the Metropolitan Railway, from the 'Illustrated London News'.

London Transport MuseumWork on the world’s first

underground railway started in 1860 when the Metropolitan Railway began

building a tunnel more than three miles long from Paddington to

Farringdon Street. It was largely financed by the City of London, which

was suffering badly from horse-drawn traffic congestion that was having a

damaging effect on business. The idea of an underground system had

originated with the City solicitor, Charles Pearson, who had pressed for

it for years. It was he who persuaded the City Corporation to put up

money and he was probably the most important single figure in the

underground’s creation. He died in 1862, only a few months before his

brainchild came to life.The first section linked the City with the railway stations at Paddington, Euston and King’s Cross, which had been built in the previous 30 years. The chief engineer was John Fowler, the leading railway engineer of the day, who would go on to create the Forth Bridge in Scotland. He did not come cheap and his Metropolitan Railway salary of £137,700 would be worth about £10 million today.

A deep trench was excavated by the ‘cut and cover’ method along what are now the Marylebone Road and the Euston Road and turning south-east beside Farringdon Road. Brick walls were built along the sides, the railway tracks were laid at the bottom and then the trench was roofed over with brick arches and the roads were put back on top, though the last stretch to Farringdon was left in an open, brick-lined cutting. Stations lit by gas were created at Paddington, Edgware Road, Baker Street, Great Portland Street, Euston Road and King’s Cross on the way to Farringdon, which was at ground level and was built, not entirely inappropriately as things turned out, on the former site of the City cattle market. W.E. Gladstone, who was Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time, and his wife Catherine were passengers on a trial trip in May 1862.

Built round the clock by shifts of navvies, the line had to avoid numerous water and gas pipes, drains and sewers. There was a problem when the noxious Fleet Ditch sewer flooded the works in Farringdon Road, but that was dealt with and on January 9th, 1863 the line’s completion was celebrated at a gathering of railway executives, Members of Parliament and City grandees including the lord mayor. The prime minister, Lord Palmerston, had declined his invitation, saying that at 79 he wanted to stay above ground as long as he could. Starting from Paddington, some 600 guests were carried in two trains along the line to Farringdon Street station, where a banquet was held, speeches made and due tribute paid to the memory of Charles Pearson. Music was provided by the Metropolitan Police band.

The line was opened to the public on the following day, a Saturday, and people flocked to try it out. More than 30,000 passengers crowded the stations and pushed their way into packed trains. The underground had been mocked in the music halls and derisively nicknamed ‘the Drain’. There were predictions that the tunnel’s roof would give way and people would fall into it, while passengers would be asphyxiated by the fumes, and an evangelical minister had denounced the railway company for trying to break into Hell.

In fact the railway was a tremendous success and The Times hailed it as ‘the great engineering triumph of the day’. In its first year it carried more than nine million passengers in gas-lit first-class, second-class and third-class carriages, drawn by steam locomotives that belched out choking quantities of smoke. The fact that the passengers were at first forbidden to smoke in the carriages was not much help.

Over the next two years the line was extended further east into the City to Moorgate and, in the other direction, to Hammersmith. Other lines were soon added to the growing network, deeper underground tunnelling was introduced and the steam trains were replaced by electric trains. The first underground electric railway, the City and South London, which ran from near the Bank of England under the Thames to the South Bank, opened in 1890. It was the first line to be called ‘the tube’ and the windowless carriages with their heavily upholstered interiors were popularly known as ‘padded cells’.

As far as the City was concerned, the corporation was able to sell its shares in the Metropolitan Railway at a profit and the underground did ease congestion for a time. A more lasting consequence was to make commuting far easier and so cause London to sprawl out even more from its centre, while the number of people actually living in the City itself declined sharply.

No comments:

Post a Comment